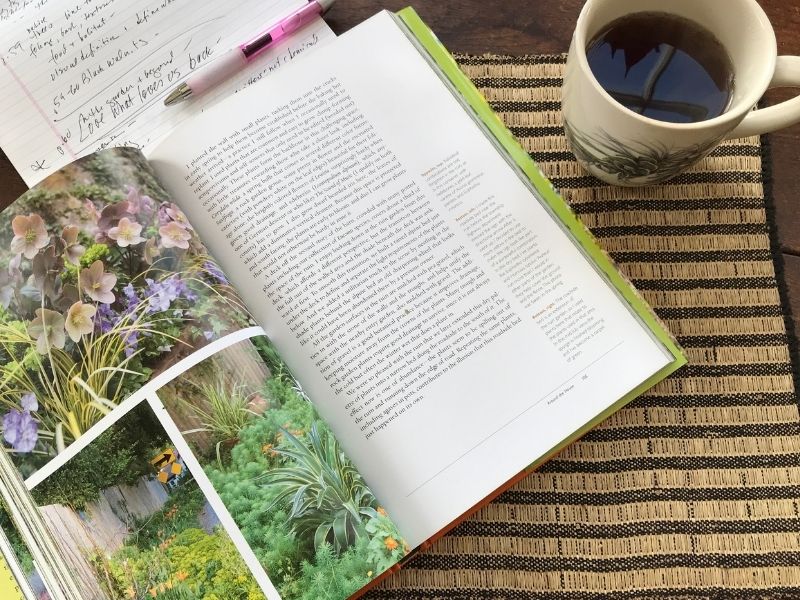

Early winter is time for musing and making notes. For assessing successes and failures in our gardens while they’re still semi-fresh in mind.

We can change course and leave failures behind – there’s always next year, right? Why not cozy up with a good book and let some new ideas take root.

Winter is a good time to enrich our knowledge, explore new ways of thinking and follow threads that we didn’t have time for when we spent our days outside doing things in the garden.

Now that ground is getting hard to dig, I’m digging into the piles of books. They’re piling up on the dining table, desk, coffee tables, the tv cabinet, by my bedside.

As I dust them off and settle into a rocking chair by the woodstove, with a steaming cup of tea, the fragrance from rosemary or orange peels on top of the stove drifts through the air.

My New Favorite Book

David Culp’s The Layered Garden: Design Lessons for Year-Round Beauty from Brandywine Cottage is resonating with me big-time as I get into musing and reflecting mode.

I will be forever grateful to David for spontaneously handing me a flat of his Brandywine strain hellebores to try many years ago. This mix of open-pollinated multicolored beauties has increased over the years.

Every single one of them is a delight (doubles are too).

This is a welcoming book, full of thoughtful observations, memories and generosity. It’s celebratory and packed with the kind of quiet wisdom accrued over years of observation, trial and error, of doing.

I find myself constantly nodding in agreement.

Culp, a noted teacher and speaker, calls himself a horticultural cheerleader, with emphasis on the cheer.

He and his partner have created a garden of complex beauty that hews to their belief in “living and working within our means and leaving a light footprint on the land.”

Many Layers

Layering, as one would guess, means, as he puts it, considering the physical space “from the ground level to the middle level of shrubs, and small trees up to the canopy trees.” It includes planting vertical surfaces, to bring flowers to eye level.

But layering exists in time as well, and Culp explains how he creates dense plantings that go from peak to quiet time to peak throughout the season. It’s like music, a romantic symphony.

Sumptuous photographs showcase gardens that look traditional, appropriate for the 1790’s Pennsylvania farmhouse they embrace.

But this book is a far cry from the tradition of what I call the “thou shalt” school of horticultural writing and advice.

Culp doesn’t intimidate beginners intent on following “the rules” and afraid of making mistakes, he encourages them. Experienced gardeners will find new ways of thinking about things too, and much useful information.

“Design lessons” only sounds like a lot of rules.

Culp’s first rule for designing a garden is that “there are no rules, at least none that everyone must follow.”

He advises making a plan to help solidify your dream, then putting it away in a drawer. “A plan made in one particular moment in time and rigidly followed will satisfy neither the gardener’s creativity nor the garden’s full potential.”

I love how, in a sidebar, “Conversations About Color” he quotes three of his horticultural heroes, all English, all pontificating. They completely disagree with each other. He embraces them all.

Chapter Two is a tour of the gardens, conveying how the layered garden works, how and why different areas came into being.

This chapter leads off with the questions every gardener needs to ask.

“What do I want from my garden? What really excites me? What do I think is beautiful? And how much work do I want to do to keep it that way?”

Lots of practical advice here:

- Screen unwanted views for privacy and appropriate mood, creating a backdrop for the garden. “A garden can be filled with the most beautiful plants on earth, but if the backdrop is a string of cars parked in the neighbor’s driveway or a woodpile covered with a bright-blue tarp, the eye will instead focus on those unattractive distractions.”

- Begin by planting the areas closest to the house, the areas you see most often, then expand outward. Feature early blooming plants there, so when you dash in and out in cold weather, you’ll see something in bloom – and you can enjoy them from the comfort of the house (especially if you eschew curtains).

- If you need to amend soil, to improve drainage, for instance, do the entire bed, rather than piecemeal for single planting holes.

- A path should be as wide as two people walking side-by-side – at a minimum

Culp’s description of how his partner took a sledgehammer to the cracked concrete floor of a collapsed outbuilding to make the Ruin Garden revived my enthusiasm for demolishing parts of my driveway to make way for plants and interesting rocks.

Underlined Insights

The insights layered with tips in Chapter 1 so echoed my own experience, I seem to have underlined half the chapter in agreement.

- A first attempt at designing one border “was not offensive, it was something worse: dull.” (The photo taken 20 years on shows a garden that is anything but dull).

- “The bottom line is that a garden should be fun… Experiment, play with colors, do what pleases you, and do not be afraid to change things if you wish.”

- “My one rule about color is that you should do what you like: that way you are assured of pleasing at least one person in this world.”

- “I have come to believe that that the shape of plants, more than their colors, is what gives any garden its drama and punch.” He advises taking a photograph and editing out color to see if textures and shapes stand out distinctly.

- Upward reaching plants and vertical man-made elements “stand out, connect the earth to the sky, and help carry the eye from space to space when repeated throughout the garden.”

Tips are woven into the narrative, as would naturally come out in conversation on a walk together through the garden. Another layer.

The conversation meanders from editing, creatures, imperfection, growing under black walnuts, to how the foliage, bark and textures of native trees link to the larger landscape.

It touches on plants that withstand drought, sedges for shade, rogueing out disease-prone plants to develop a strain of resistant ones.

The stroll informs and delights – including a fond tribute to “insectivorous mobile garden art” (chickens).

Read the book for ideas, dip back in to discover plants for all seasons, but do take to heart Culp’s words in a passage on failures and plants that don’t want to grow in his conditions.

“It is good advice, in the garden and beyond, to love what loves us back, and not covet what loves the gardens of others.”